Q&A

Q&A

Sensory deprivation did not put the brain to sleep: It opened up a panoply of altered states that emulated dolphin consciousness and launched the cultural revolution of a generation

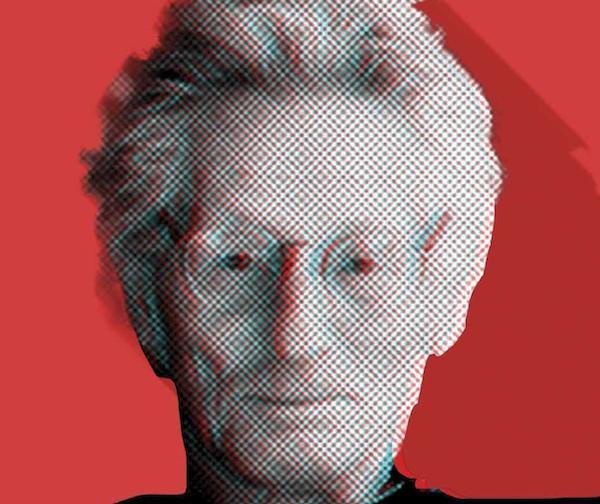

John Lilly on Dolphin Consciousness

by Judith Hooper

|

Above the ranch-style dream houses and seafood restaurants along the Pacific Coast Highway the rugged, bleached Malibu canyons, twisting roads, dusty scrub oaks, and desert sagebrush speak a supernal language. It is a landscape of the spirit more than of the body, and Dr. John C. Lilly, dolphin magus and scientist-turned-seeker, seems at home here — where the spectacular surf down at Zuma Beach is a mere rim of white foam on the edge of the world. If life imitates art, Dr. Lilly should live on just such a mountaintop.

It hadn't been easy to find him. When I asked scientist acquaintances about Lilly's whereabouts, most of them said something like, "Do you mean, what dimension?" Someone thought he worked with dolphins at Marine World, in Redwood City, just south of San Francisco, and, it turns out, he does. But when I phoned there, I talked to a succession of secretaries who had never heard of the remarkable Dr. Lilly. I finally left a message with "Charlie," a gate guard who told me that he sometimes "sees him go in and out." No luck. When at last I called his house in Malibu, Lilly answered the telephone himself and gave me road directions that were accurate to the tenth of a mile. Lilly's autobiography, The Scientist (1978), begins with the creation of the universe out of cosmic dust, but his own human chronicle starts in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1915. A scholarship whiz kid at the California Institute of Technology, Lilly graduated with a degree in biology and physics in 1938 and went on to earn his M.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. Though he became a qualified psychoanalyst, his first love was brain "hardware." His mastery of neurophysiology, neuroanatomy, biophysics, electronics, and computer theory gave him something of the technical ingenuity of the genie in The Arabian Nights. From 1953 to 1958 he held two posts — one at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and one at the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness — both part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in Bethesda, Maryland. In his early years at the NIH he invented a technique that allowed scientists for the first time to take brainwave recordings from the cortex of unanesthetized animals. He also mapped the brain's pleasure and pain systems by direct electrical stimulation of its core regions. And in 1954, tackling the classic puzzle of what would happen to the brain if it were deprived of all external stimulation, he built the world's first isolation tank. Floating in his dark, silent, saltwater void — the original version of which required that he wear a skindiver's mask — Lilly discovered that sensory deprivation did not put the brain to sleep, as many scientists had supposed. Furthermore, tanking led him far afield from the doctrine that the mind is fully contained within the physical brain. The tank, he declared, was a "black hole in psychophysical space, a psychological freefall," which could induce unusual sensations: reverie states, waking dreams, even a kind of out-of-the-body travel. (Today, of course, isolation tanks are so much a part of the culture that even straitlaced businessmen routinely spend their lunch hours — and upwards of $20 — relaxing in health-spa tranquillity tanks based on Lilly's original design.) More and more enamored of the deep, womblike peace he experienced in the tank, Lilly began to wonder what it would be like to be buoyant all the time. Whales, dolphins, and porpoises sprang to mind, and the rest, of course, is history. By 1961, Lilly had resigned from the NIH to found and direct the Communications Research Institute, in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Miami, Florida, for the purpose of studying these big-brained, sea-dwelling mammals. Convinced that dolphins are not only smarter but more "humane" than Homo sapiens and that they communicate in a sophisticated sonar language popularized, rather inaccurately, by the baby-talking dolphins of the film Day of the Dolphin — Lilly began a lifelong quest to "talk" to the Cetacea. Today he uses a "two-faced" computer system called JANUS — named after the two-faced Roman god — to work out a human/dolphin language.

While Lilly was experimenting with otherworldly states in the isolation tank, the halcyon days of hallucinogenic research were under way at the NIMH. (LSD was not to become a controlled and, therefore, sticky substance until 1966.) Lilly, however, did not try LSD until the early 1960s. Once he did, it became his high mass. Mixing LSD and isolation tanking for the first time in 1964, he entered what he described as "profound altered states" — transiting interstellar realms, conversing with supernatural beings, giving birth to himself, and, like Pascal, exploring infinities macroscopic and microscopic. "I traveled among cells. watched their functioning By all accounts. Lilly has probably taken more psychedelic substances — notably LSD and "vitamin K," the superhallucinogen he prefers not to identify — than anyone else in the consciousness business. Since the lords and overseers of establishment science frown on using one's own brain and nervous system as an experimental laboratory, Lilly today reports his findings in popular books instead of in neurophysiology papers. He makes the scene at such New Age watering holes as Esalen, in California, and Oscar Ichazo's Arica training place, in Chile. He hasn't received a government grant since 1968. When asked about him. mainstream scientists tend to shake their heads sadly, as if recalling someone recently deceased. "The trouble with Lilly is that he is in love with death," says one neuroscientist friend of his. "But, God, is he brilliant!" Yes, he is brilliant, and, yes, he does seem to have flirted quite flagrantly with death. Though LSD- or K-related accidents have almost killed him on at least three occasions, Lilly still keeps going back to the void, once tripping on K, he tells me for 100 solid days and nights. It is also true that he has always returned to Earth, however constraining its boundaries, and that his wife, Toni, has had a good deal to do with that. The moment I arrive at his house, having driven my rental car over zigzagging mountain roads, Lilly announces, "We have one rule in this house. No one can take drugs of any kind and drive back down that road." Five minutes later he seems to be offering me acid and K — or did I hallucinate that? Is he putting me on? What kind of game is he playing with the anonymous reporter who has come to call? He tapes me with a matchbook-sized Japanese tape recorder while I tape him: The phone rings and Lilly answers it, his face as immobile as the wooden Indian that guards his entryway. "Who are you?" he demands. His side of the conversation is curt. "It was someone asking about the solid-state entities," he tells me. As our interview proceeds, I watch various expressions play across his patrician, chiseled-granite face — unexpected sweetness whenever he speaks of Toni, or of dolphins. (When talking about a dolphin, Lilly always uses the pronoun he, never it.) Sometimes his language is full-bodied, and poetic; sometimes it is a private blend of computerspeak and Esalenese, full of phrases like "Earth Coincidence Control Offices," "metaprogrammings," and "belief-system interlocks." My own questions echo in my head, and Lilly seems bored, on the verge of walking off abruptly into a zero-g universe of his own. Possibly to get rid of me for a while, he escorts me to his samadhi isolation tank. In this warm, saline sea of isolation, where such luminaries as Nobel physicist Richard Feynman, anthropologist Gregory Bateson, psychologist Charles Tart, and est czar Werner Erhard have floated and had visions, I try to sort it all out. My visions are disconnected, rudimentary: I am a swamp plant trailing its leaves on the water; a fetus; a dolphin; a whirring brain in an inert shell. An hour and a half later (one loses track of time) I emerge and try to continue the interview. The problem is, in my state of tranquillity, I have lost interest in asking reporterlike questions, and, besides, I feel Lilly retreating more and more into some remote, glacial space behind his eyes. From another room a manic laugh track from what sounds like an old I Love Lucy show floats out to us. Some time later Toni Lilly suddenly walks in, smiling and carrying bags of groceries. Her husband jumps up to help her unload the car, and I take my cue to depart back down the mountain.

Only later, at home in the Los Angeles lowlands, do I notice that I am altered — that for 24 hours after isolation-tanking, reality looks and feels quite different. Four weeks later I telephone Lilly, and we talk again. The following interview is the result of our afternoon together in his Malibu home and of that subsequent telephone conversation.

|

photo illustration by Henry Bacon

|

This article copyright © 1983 by Judith Hooper. Used by permission. Photo illustration copyright © 2016 by Henry Bacon. All rights reserved.

Join the OMNI mailing list

Tweet